More Than Our Crimes co-founders Pam Bailey and Rob Barton (who is currently incarcerated at a federal high-security prison in Florida) recently had a wide-ranging conversation about why so many prisoners fight among themselves, but don’t do what it takes to hold the prison administration to account. We thought our readers would be interested in the topic. Below is an edited transcript.

Demanding accountability

Pam: I’ve noticed a common dynamic in prison: There are a lot of fights between prisoners, particularly between the members of one car (gang) and another. Yet most prisoners won’t file grievances against the guards and other prison staff who mistreat them. I get that it’s unusual to win a grievance, but that’s the game you have to play to get to court, where real change can happen. I know a few guys who file, but they aren’t the norm. Why?

Rob: Most of us come from the streets, and when we think of fighting, we think of fighting back physically. It’s been ingrained in us since childhood. We feel as if we’ve never won anything any other way. Our families didn’t vote and now we don’t file grievances, because we think it’s not going to change anything, so what’s the point? But what we’re really doing is throwing away our power. Because I do believe that if we came together as a voting bloc, for example, we could have some success.

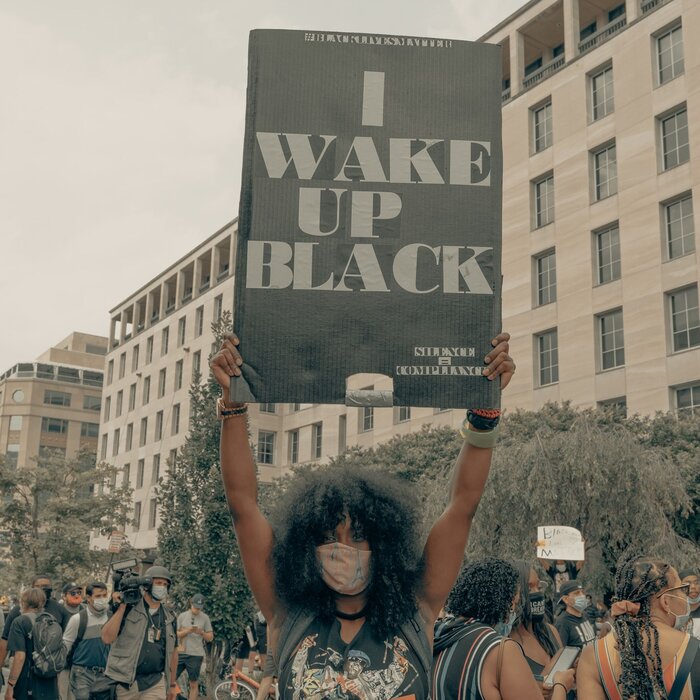

There’s another root cause of this passivity. I think it also comes from not really knowing our history. A lot of us don’t learn the history of radical Black America anymore. In part, that’s because racism isn’t as overt as it used to be. Sure, there are incidents like the police killing of George Floyd, but it’s not like in the 60s and the 70s when Black people couldn’t eat at certain counters, use certain restrooms and sit in certain bus seats. Now, people are more apt to blame the system and not racism.

The result is that no one is willing to make the necessary sacrifices. We are taught that being American means protecting our individualism, with every person looking out for their own interests. We’re so blinded by the lure of money and other material things that we don’t come together to fight for something that’s worthwhile. What is lost, and why history is so important, is that all the civil rights wins – the abolition of slavery, the vote, etc. – we got by coming together.

In the prison context specifically, we’ve learned that when something happens to the police, we’ll be punished severely. Actually, that’s not just in prison. Look what happens when someone kills a member of the police (they typically get the death sentence or life without parole) vs. when an officer kills a Black person. The message is that the life of a police officer is more valuable than that of a “regular” person—and certainly more than a Black man’s. The establishment wants us to know there will be severe punishment for fucking with them. So, it’s become ingrained in our self-conscious that we can’t fight the system.

Pam: It used to be different, like in the time of the Attica prison riot in 1971 and the Huntsville Prison Siege in 1974. What changed?

There was a different consciousness then. The civil rights protests were at their peak. People in Africa were struggling against colonialism. That was the spirit of the people and it trickled down into the jails. Today, we don’t feel oppression as directly. We’ve lost the personal connection to our history and thus the drive to come together. And the government has played into that. Government agents infiltrated our organizations and broke them up, kept us separated. That’s why a voting bloc is so important.

Cultural education

Pam: How did you learn about African American history?

Rob: My mother started me on reading and writing when I was just yay high. And since then, I’ve always been thirsting for knowledge. So, when I came to jail, I started reading all different types of books. I think one of the first books I read was “From Niggas to Gods,” and that led me to reading about African history, which led me to the civil rights movement. I developed a thirst for my history that way. It’s important because history repeats itself. People in power always use the same tactics.

Pam: So, it was incarceration that reconnected you to your history?

Rob: I knew about Martin Luther King from school, of course. But essentially, yeah, I didn’t really know my history until I came to prison. I’m talking about the Black Panthers, George Jackson, Malcolm X and Nat Turner, for example. It’s important to learn about the radicals too, because I think the reason the government was forced to give in and give us certain rights in the 60s was that in addition to Martin Luther King, there were Malcolm X and the Panthers. The government didn’t want to deal with that side of the movement. If it wasn’t for Malcolm X, Martin Luther King wouldn’t have made the progress he did.

Martin Luther King Jr. came from a middle-class family and he thought what Blacks needed was the opportunity to go to good schools and assimilate into American culture. But when King started going into the ghettos and saw what was really going on, he realized that change was needed in the entire American social system. He started speaking out against the war and tried to create a poor people’s movement. That was the revolutionary Martin Luther King they don’t want us to know. And I think that’s why he was killed.

Pam: How did you get these revolutionary books in prison?

Rob: I’d get the books from the older guys, or maybe they were left behind and made their way to the book cart. A lot of the guards don’t know what they’re allowing us to read!

Pam: But you say a lot of the guys in prison today aren’t reading the books you did. Why? Can’t you host some book-discussion groups?

Rob: No. That’s what’s missing. I hear they used to have them in the 60s and 70s. Now, when older guys give me their books and I try to share them with the younger guys, they say, “Man, I’m not on that Black shit.” It’s not popular or cool; what’s cool now is the hip hop/rap culture. Again, I think that was somewhat the government’s hope or even its plan. They killed our parents and put drugs in our neighborhood; what drives kids now is materialism: money and image.

That mentality carries over into jail. Most people don’t file grievances because they figure, if they aren’t going to benefit directly from it, why risk anything? So, what happens is nothing. That’s what brings us back to the importance of our history. People made sacrifices for us. People gave their lives so we can do the things we do today, like vote. D.C. people need to realize that they have been given a great power, to vote while still in prison. There are a lot of laws that impact us and we need to express our opinion by voting. But a lot of D.C. guys haven’t even registered, because they don’t feel like the system is for us, or they think the only time politicians pay attention is when they want something. So, again, nothing happens and we complain. Same with grievances. We complain about lockdowns, but the guys who will file are few and far between. We won’t even come together in a meeting and talk about how we can do something about it. We think we won’t be able to win, or that we only get something when we act out physically. And that only brings more repression. We end up with nothing.

Relationships with power

Let me ask you a question, Pam. How do you feel about doing all this work for us when we won’t fight for ourselves?

Pam: I had this same conversation with Palestinians in Gaza when I lived there. Remember the quote from Frederick Douglass: “Power concedes nothing without a demand.” Throughout history, nothing big has been won in terms of civil rights without people making sacrifices. And, yes, that does usually mean that some of the resisters are going to get in trouble—maybe even lose their lives. We should be thankful that there are people willing to do that. Because if everyone just lays down and goes along, that’s what the oppressors hope you’ll do. Of course, it’s easy for me to say that.

But what’s equally frustrating is that while a lot of prisoners aren’t willing to risk filing grievances, or stage a hunger strike, they are willing to fight each other over almost anything. What’s that all about?

Rob: It’s because we’re unconscious. And we aren’t connected to our history. The sad truth is that if I beat up my brother, there won’t be any real repercussions. I can take a guy’s money and someone will try to kill me for it. But if the police come and do the same thing, the guys won’t do anything. That’s because they know they’ll lose if they fight back against the police. Sure, if they retaliate against one of their own, they may go to the SHU (special housing unit, or “hole) or the ADX (super-max solitary prison), but most of us are willing to do that to maintain respect among our own.

Pam: It wasn’t always that way though. George Jackson refused to knuckle under because he knew the other prisoners looked to him as an example. And then there was Albert Woodfox, who led a strong Black Panther cadre in Angola prison. He was punished for it but stuck by his principles.

Rob: Like I said, you just don’t have that type of consciousness in prison anymore. It’s gone on the streets and it’s gone in jail. But we need to get back to it.

A call to action

Pam: A lot of people are surprised that in some of the police beatings of Black men, the killers were Black themselves. The most famous recent case was the murder of Tyre Nichols in Memphis by five police officers—all Black. Do you think the culture of being a cop trumps everything else? Or is it that, as you said, “it’s okay to beat up one of your own”? Or both?

Rob: It’s implicit bias even among Blacks. Remember that case of the 13-year-old Black boy in DC who was shot by a middle-class Black government employee who said the kid was breaking into cars? The man’s only thought was about protecting his property. He didn’t see a little Black boy who probably had a troubled childhood. He saw a criminal, and that happens a lot. The lack of consciousness is pervasive.

We need to come together, we need to vote, we need to file grievances. You know, several prisons or prison units have been closed due to their notoriously bad conditions. Examples are USP Lewisburg and the special management unit at USP Thomson. Those victories weren’t won via physical fights. They closed because prisoners spoke out. The pen can indeed be mightier than the sword. But we don’t it as much as we should, and we lose.

Pam: What happened with Thomson is indeed a good example of how people inside prison can partner with people outside: Prisoners and their family members were willing to be quoted, to speak out and tell their stories, despite some risk. NPR and the Marshall Project publicized their reports, and that got the attention of Congress. Via More Than Our Crimes, we are trying to bring similar attention to the Hazelton complex in West Virginia, where we have a lot of brave prisoners and their families willing to speak out about the prolonged lockdowns and substandard medical care. So far, we’ve seen one promising result: Sen. Joseph Manchin, otherwise a very conservative Democrat, has signed on as a co-sponsor of the Federal Prison Oversight Act. Together, I do believe we can make a difference.