The late, legendary Hall of Famer Paul Robeson once said, “You can limit my mobility, but you can’t limit my mentality.” Leonard Bishop is a testament to this truth. Although his body is languishing for a third decade in the bowels of the American carceral system, he stands firm in his belief that even in the face of barriers like the impenetrable walls of prison, we each can shape the world around us. And he has. Bishop is one of the few people in the country who has served as an elected government official from behind bars.

After two journalists and editors I work with asked if I was familiar with Mr. Bishop, I decided to seek him out. Once introductions were made, the first thing that struck me about him was his quick wit, lack of pretension, and eagerness to engage in deep discussions about DC politics and prison reform. Through our many revealing discussions. I concluded that he is one of many DC men who may have lost their way, but now have learned a wealth of life lessons that can help heal and guide others who have stumbled off the path. The interview that follows is a sampling of our cultural and political discussions.

Civic engagement behind bars

Askia Afrika-Ber: While in the D.C. jail awaiting the results of your re-sentencing hearing, you were elected to represent the population as Advisory Neighborhood Commissioner (ANC). That’s a position that’s unique to D.C., but I think a lot of our brothers here don’t know what that is. What were your duties? And how did that help the people in the jail?

Leonard Bishop: The ANC was created to connect residents at the neighborhood level to the DC Council, so they’d understand local interests and our voices would be heard. The jail, with its more than 1,000 “residents,” is recognized as a district of its own within ward 7 and last Jan. 1, I was just the second person (after Joel Castone) elected to lead it as ANC. My responsibility was to be present at multiple town hall meetings held throughout the Department of Corrections (DOC) facilities, and to listen with an objective ear to both grievances and ideas. That input was instrumental in opening the lines of communication between staff and incarcerated residents. And it helped improve the quality of educational programming, recreational activities and the maintenance of the facilities.

For example, I had a direct line of communication with DOC executive staff, and I used it on several occasions. One time stands out in my mind: I don’t remember how I learned of the issue, whether it was through email or a town hall discussion, but the outgoing mailbox in the women’s program unit had been taped up for over a year. The female residents were unjustly made to show identification to staff whenever they needed to send mail, legal or otherwise, and their letters were only collected once or twice a week, if that.

After reading the relevant policy, I learned that DC supposedly has zero tolerance for gender discrimination, yet the DOC’s own policy wasn’t being followed. I inquired about why the slot for the women’s mailbox was taped over. That meant the women had to wait until a CO came around to collect the mail, and if they were in the shower or using the toilet at the time, they had to rush out, clean up and grab their IDs so they could catch him or her. Turns out, the persons involved in closing the mailbox had received incident reports a long time ago, yet it remained closed. So, I climbed the chain of command. Now, here’s the funny part: Although I didn’t receive a direct response from any of the individuals I contacted, several days later, the tape was removed, making the mailbox once again available for use. What I learned is that our legitimate grievances tend to be ignored because they aren’t being presented by and to the right people.

Askia: Many of the public servants elected to the DC Council are highly educated career politicians. How well do you think you were able to fit in and represent us by addressing prisoner rights and criminal justice reform issues?

Leonard: Initially I was a little intimidated by the other officials’ educational backgrounds and political titles, etc. I am an autodidact, I have a “homemade” education like Malcolm X. During my swearing-in ceremony, I met Charles Thornton, head of the Corrections Information Council. This elder statesman offered to buy my suit for this monumental occasion, but even better, he gave me a bit of priceless advice that has radically changed my perspective of myself: “Move with confidence whenever you step into these rooms, knowing that you are an expert on what goes on behind these walls. It’s now your duty to provide the city council and mayor with the truth.”

Askia: Do you think you should have been allowed to stay in the DC jail indefinitely so you could finish your full term as the ANC?

Leonard: A resounding YES. I don’t think I should have been treated any differently than any other elected official. Without question, I should have been allowed to serve out my full two-year term in the DC jail. I wrote everyone imaginable in the hope of remaining at the jail to finish what I had been elected to do. I sent letters soliciting support to various city council members, the mayor and even the U.S. Marshals Service. I was crushed and felt let down when I was forced to leave the DC jail. I was passionate about the work and wanted to demonstrate my worth to my community. I had a vision of what we could accomplish for both criminal justice reform and public safety.

Askia: What will it take to motivate incarcerated and recently returned DC residents to register and vote?

Leonard: We need our elected officials and candidates to carve out time from their campaign schedules to speak directly with us, so that we can get acquainted with them and whether they represent the best interest of this community and their families. We need relevant information flowing in via mail and email, educating us on candidates’ backgrounds, policies and political views so that we can make educated decisions when casting our votes. I think we are at least worthy of that. Information is key.

Askia: Now that you’ve gotten a taste of political clout, do you see yourself re-entering that arena upon your release?

Leonard: Yes, of course. I honestly feel that I’ve found my calling in politics. I’m not going to lay out my blueprint for the future, but I’ll leave you with this: I haven’t even scratched the surface of what I believe I am going to accomplish.

How DC can support incarcerated residents

Askia: Local government officials often say they aren’t responsible for us because we’re in the custody of the federal Bureau of Prisons. But we grew up in DC, we’re still District residents and most of us were convicted under DC law. And now we can vote. What do you think the DC government should do so it can better serve our community?

Leonard: The best way for the District government to support us is to re-exert total control of its incarcerated residents. And the only way they can accomplish this is to build our own prison complex. That way, they would be able to oversee and manage our rehabilitation, medical care and reentry into the community, which would in turn benefit public safety. DC cannot continue to allow the federal Bureau of Prisons to manage its prisoners, who will eventually return to the nation’s capital. If DC men and women who are temporarily incarcerated in the FBOP are mistreated and abused, forced to participate in racial and gang riots, and must constantly be on alert for possible knife and fist fights, what do you think will be their emotional and mental state upon release? DC needs to build its own prison and make it a model for the rest of the country.

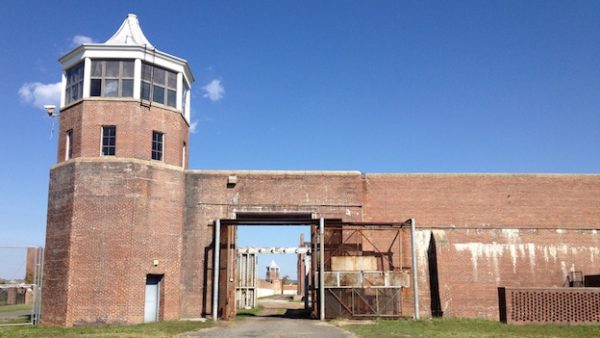

Askia: As you know, DC once had its own prison; it was called Lorton and was located in Virginia. But in 2001, local officials closed Lorton and gave responsibility for the housing, care and management of District prisoners to the FBOP. Those of us who spent time there know how really violent Lorton was. But based on your previous answer, I assume you think it was wrong to give up a local prison.

Leonard: It has caused a great deal of disconnect and disruption between DC prisoners and their families, even severing the relationships of many District residents with their supporters on the outside. I remember like yesterday how every single Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday and Sunday, the visiting room behind the wall, the maximum-security section of Lorton I was housed in, was always packed and loud with the hum of conversation between loved ones and the playful sounds of children’s laughter. Since coming to the feds, those visits are only cherished memories. The feds place such stringent security restrictions on visitor entry that many prisoners simply refuse to ask their family to bother making the hike. Then there’s also the distance between our actual homes and the prisons, and the cost in time and money. Even if they can afford it, they risk being turned away after traveling hundreds of miles, prohibited from entry due to a lockdown or some outrageous reason like the detergent used to wash their clothes being falsely read as narcotic residue.

And then there is the (lack of) medical care. In 2010, when I was at USP Florence in Colorado, I was diagnosed with Burkitt’s lymphoma, a rare form of cancer that attacked my immune system. You know when something is wrong with your body, and for two months, I went to the medical department to lodge complaints about the recurring, excruciating pain in my abdomen. But the staff went so far as to threaten me with incident reports and even told me I could be placed in the SHU (solitary confinement) if I kept coming so frequently. Fortunately, I eventually defeated it on my own.

I have watched numerous men die miserable deaths, alone in solitary or in a prison hospital bed, hundreds of miles away from home. The BOP is so overcrowded and the quality of medical care so poor that the medical department tells prisoners flat out that if their problems aren’t life threatening, they will not be seen by an outside treatment specialists.

Askia: One of the recurring reasons cited by judges when they deny a DC resident’s resentencing petition is “institutional misconduct,” often because of altercations with prisoners from another part of the country. Care to elaborate?

Leonard: I am 100% certain that most incident reports for assaults, possession of a knife, etc. would be nonexistent if Lorton hadn’t closed. The ill-conceived decision (a result of economic mismanagement and indifference) to place DC prisoners in the feds put us in the middle of an unfamiliar, hostile, gang land. Many of the racist white and Mexican gangs are renowned for targeting DC prisoners, not just due to the color of our skin but also because of where we’re from. If we had been allowed to remain in our own prison system, DC prisoners would’ve had more opportunity and the time to focus on rehabilitation instead of self-defense.

Congressional interference in DC

Askia: Recently, Congress and President Biden refused to allow DC to enact its revised criminal code. What are your thoughts on this matter?

Leonard: I think it was a mistake for Congress to meddle in DC’s affairs, although by law it has oversight power over the District of Columbia. Nevertheless, DC home rule should carry some weight. Everyone agrees that our criminal code is severely outdated and filled with relics from the Jim Crow era. The congressional interference had nothing to do with a serious consideration of the code; rather, it was a political ploy, caused by an ongoing feud between the DC council and the mayor and between the DC government and right-wing members of Congress. Although Mayor Bowser went before Congress to testify in support of home rule, her public opposition to the bill, which she labeled “soft on crime,” gave the President Biden the green light to sacrifice the bill. Our council invested a decade and countless taxpayer dollars into the research and development of a new criminal code and it is disgusting that our mayor made DC look unfit to govern ourselves simply because the council passed the bill in opposition to her. (Long live the legacy of Mayor Marion Barry!)

So, while Congress and our local council members continue to squabble, DC residents are neglected and struggle with poverty, while our youth get shipped to penitentiaries instead of prepared for college and university.

Incarceration and mental health

Askia: I was housed at USP Big Sandy in Kentucky at the start and conclusion of the nightmarish COVID pandemic, and the fear of the unknown and the FBOP’s nationwide lockdowns (designed to prevent the spread of the virus) put a tremendous strain on my psychological and emotional health. What do you recall of your experience while you were in the DC jail and how did you endure?

Leonard: I didn’t experience the lengthy lockdowns like my fellow prisoners, and contracted COVID on three separate occasions.

Fortunately, I was selected to work two prison details: as a mentor and a commissary worker. My work as a commissary orderly gave me access to the entire prison population, distributing pre-ordered soap, deodorant, toothpaste and food supplies. That mobility allowed me to gain a greater understanding of the toll of COVID. Prisoners watched the death toll steadily increase in the free world and grew fearful for their families and themselves. Medical care was inadequate, and prisoners began accusing staff of bringing the virus into the jail in the first place, with total disregard for prisoners’ health and safety.

At one point, it was a challenge just to get a clean face mask, get staff to wash our clothes and bed sheets, pass out cleaning solution for sanitizing our cell walls, toilet and sinks. Meanwhile, the ventilation system was outdated, dysfunctional and filthy. Psychologically, the situation was emotionally draining.

Askia: For many state and federal prisoners, it is extremely difficult to maintain healthy relationships with family and friends in the free world, and it’s even more complicated to parent while incarcerated. How have you been able to handle the challenge of sustaining these vital emotional connections?

Leonard: My daughter was five months young when I was arrested. Understanding that I was responsible for another life while I was incarcerated, I give all credit, praise and my sincerest thanks to my daughter’s mother and my immediate family for keeping the line of communication open and for always keeping me abreast of her wellbeing. For any child, life with an incarcerated parent is a rather ugly reality. Nevertheless, the difficulties of her early childhood development were helped with frequent phone calls, birthday cards and lengthy letters in which I made sure she knew how unconditionally I loved her. I answered any question she had for and about me and was always ready with fatherly advice.

I also made a conscious decision at the onset of my sentence that I would not be a financial burden on my family. Anything that anyone has ever done for me was done not out of obligation but out of love. In prison I developed a productive work ethic and cultivated a collection of skillsets that allowed me to generate capital and take care of myself, even occasionally sending money to my daughter’s mother.

Askia: In a 1975 Playboy magazine interview, Muhammad Ali once said, “The man who views the world at 50 the same as he did at 20 has wasted 30 years of his life.” Do you agree with that?

Leonard: I agree, without a shadow of doubt. It’s part of human development. Everything must grow, everything must change, nothing and no one stays the same. I came to prison at 19 years young and am now going on 50. Nothing about me is the same, from my health, my understanding of myself, my thought process, to the daily decisions I am forced to make to stay safe.

Askia: In contrast to residents of state and private facilities, federal prisoners are prohibited from having TVs in our cells. Thus, many of us have been transformed into avid readers of a vast assortment of books, magazines and legal texts. How many books do you read in a month and who are some of your favorite authors?

Leonard: Since I’ve returned to a federal penitentiary from the DC jail, I haven’t been reading as frequently as I’d become accustomed to. I am still a little shellshocked about my removal from the jail and my elected ANC position, which was a very productive environment for guys like me who have post-conviction matters before the court. USPs have zero re-entry programs (besides RDAP or the Challenge programs in selective prisons), zero vocational or higher-learning programs available for the prison population. The DC jail and its progressive re-entry department was a breath of fresh air. College courses, self-help programs and being near my family were truly therapeutic.

In those five years spent in the DC jail, I had a sociopolitical revelation. I’ve come to believe with every fiber in my body that prisoners can, with self-determination and a support group, reinvent themselves for the better. Two of my favorite books are “Standing on the Scratch Line” by Guy Johnson and “The Secret” by Rhonda Byrne.

Askia: I understand that prior to being transferred to the DC jail in pursuit of post-conviction relief, you worked as the head cook at USP McCreary. Is cooking a passion of yours, and if so, where did you acquire your culinary talents?

Leonard: Damn near all my mother’s children know how to cook or bake. My first introduction to cooking came from standing around listening to the timeless sounds of Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye and The Temptations, while observing my mother and the elders prepare festive family meals in the kitchen. The first thing I remember cooking for myself was scrambled eggs. But it wasn’t until I came to prison and started cooking for others that I realized I am a natural and that I take great satisfaction from preparing meals that others look forward to. Over the years, cooking has become a form of escape for me. I get into my zone when experimenting with new recipes, blending different seasonings and smells. I look forward to cooking holiday meals at home with my family, just like my mom did. I want to keep the family tradition, her memory and her recipes alive.

Askia: Being a Chocolate City citizen myself, I can’t let you go without asking this final question: After being incarcerated for over three decades, on a scale of 1 to 10, how much do you miss the sounds of DC go-go music?

Leonard: I miss the sounds of go-go music and the go-go scene 100%. Like they say, rap speaks to what’s going on with youth culture, particularly African Americans in the struggle. DC go-go speaks directly to our youth and what’s going on in the heart of the city. I feel like go-go celebrates the rhythm, swagger and artistic beauty of the Chocolate City.

We can’t allow gentrification to mute go-go culture. I also feel like the Go-Go Museum is long overdue; I wish it would be built on the national mall so the entire world could see and appreciate how brilliant we are