There is a saying among the guys in my prison these days that goes, “The only consistency here is inconsistency.” This is a huge problem for people who are incarcerated, since everything we do is usually dictated by a schedule. When this schedule is regularly broken, and we don’t know when or even if we are coming out of our cells, it affects our ability to participate in programs essential to our eventual release, buy items at the prison store that we need for both nutrition and hygiene, and—most importantly—our peace of mind.

Lockdowns have become a daily reality, not only here at the Coleman prison in Florida, but across the country. We haven’t let been out of our cells (sort of like animals in a zoo) during the 8 a.m.-4 p.m. shift on the weekends in over five months. (A lot of the time, we don’t come out period. And if we do, it’s only in the evening on either Saturday or Sunday.) As for the weekdays, we’re supposed to be allowed out at 6:30 a.m. But lately, our doors aren’t opened until 8:30, 10:30 or sometimes 1 p.m. Once we’re out, sometimes we’re sent back to our cells due to some type of “emergency,” like when a two-hour-watch inmate doesn’t check in. (For security reasons, some individuals must physically check in with staff every two hours.) It’s starting to seem like we are always behind our doors. Guys are being hurt in fights over the smallest of things: the inability to make a phone call, access to the computers, even what’s on the TV, mostly because we’re at our mental breaking point.

This shit is driving us crazy. What the hell is going on?! The answer is always “not enough staff.”

I talked to the captain on my unit the other day, and he said he is severely short of staff; his employees are working 16 hours a day, four or five days a week, and that’s just too much. I agree. I’ve seen the impact firsthand. I find myself wondering when some of the officers ever go home, since I see them here all the time. When do they have time for themselves, for their loved ones, for their kids?

But I can’t help but also ask, isn’t anyone worried about the impact on us?

The local union chapter for government employees recently organized “an informational picket” (it’s illegal for BOP staff to strike) to explain how understaffing is resulting in overworked staff who aren’t able to deal effectively with assaults by prisoners – thus endangering residents as well. A local newspaper article was headlined, “Picket will be aimed at warning residents of danger lurking behind prison walls.”

Peyton Perry, legislative coordinator for Union Local 506, is quoted in the newspaper as saying, “FCC Coleman is short staffed by 100 officers. This translates to 554 officers split between five institutions and five shifts, attempting to supervise 6,219 individuals convicted of committing crimes such as murder, drug trafficking and sexual violations of our most vulnerable population, children.”

Wait, what? So, the people housed in Coleman are vicious, evil criminals of the worst sort (including myself), and our mental health and safety don’t matter. It doesn’t matter that we have to spend hours more in cells so small that we’re almost on top of our cell mates, smelling each other’s fumes in the toilet in the corner. It doesn’t matter that we have even less time for 120 men to call their girlfriends and wives using just five phones (with one often not working). It doesn’t matter that we miss the classes we need to earn GEDs, develop new skills and kick drug habits. And it doesn’t matter that we miss our time to buy the food items we need so we don’t go to bed hungry (because the prison-supplied food is so meager).

The other day, when the prison unexpectedly called a lockdown and ordered us back to our cells, I watched a grown man take a deep, ragged breath as he slumped on the floor in front of his door, banged his head on the wall, and hollered, “Damn…lockdown…lockdown…lockdown…that’s all they do around here is lock us down! I am sick and tired of this shit!”

It feels like lockdowns are consuming our souls. It’s discouraging some guys from even enrolling in programs. It’s straining our personal relationships outside. And our physical health is suffering too, since we’re always cooped up in our cells.

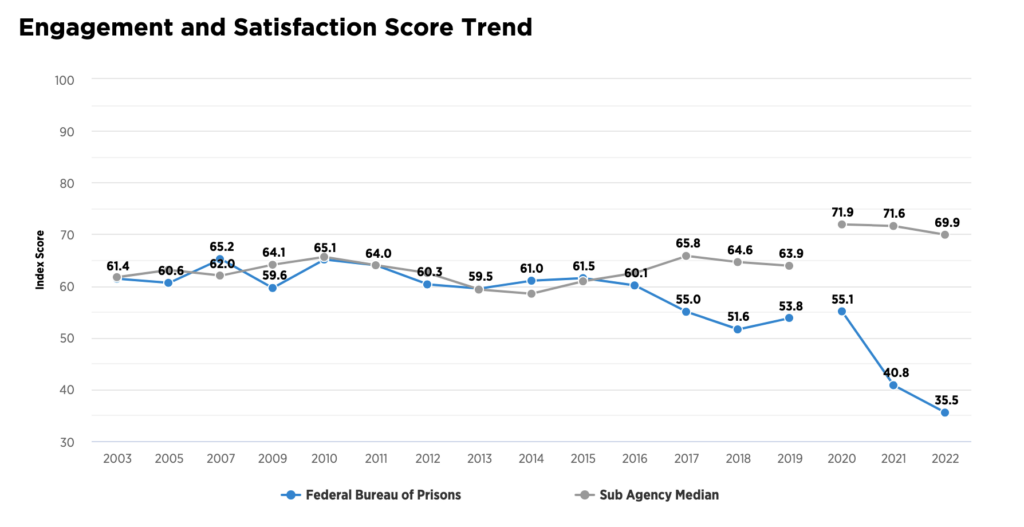

So, what’s to be done? The Bureau of Prisons needs to start asking itself why it’s so hard to recruit new employees. The Partnership for Public Service and the Boston Consulting Group recently released the results of an annual survey of federal government workers that assessed which agencies have strong employee morale and which do not. And guess what? Among sub-agencies (the Bureau of Prisons is a “child” of the Department of Justice), the BOP ranked dead last – 432 among 432. (Maybe it’s not just the pay, but also the culture?)

But there is a bigger picture: I believe the root cause of all this is not understaffing, but the fact that America is locking too many people up in the most punitive of institutions, the penitentiaries. Before the 1994 crime bill, which played a huge role in the explosion of the prison-industrial complex and mass incarceration, there were only six penitentiaries (Lewisburg, Leavenworth, Terre Haute, Long Park, Atlanta and Allenwood). Most of the people housed there had lengthy sentences. But today, because there are so many more penitentiaries (17), there are guys there doing time for just a few years or even six months for parole violations. That’s because the BOP changed the point system to make more people eligible to be placed in a penitentiary.

We need to recognize that what’s good for prisoners is also good for staff. We need to transfer more people out of these high-security hellholes that breed violence by their very nature, to facilities with staff focused on actual rehabilitation. And we need to send more people home who have spent decades behind bars with no discernible benefit to themselves or the country.